Reverse Engineering the PROM for the SGI O2

Since the early 2000s, the potential for upgrading the CPU in the Silicon Graphics O2 with a 900 MHz RM7900 has been blocked by the inability to modify the PROM firmware. To that end, I built ip32prom-decompiler, a program that decompiles the PROM into sources that can be reassembled into a bit-identical image. The decompiler goes to great lengths to produce assembly that is understandable and modifiable by replacing known constants, recognizing and replacing memory addresses with labels, inserting comments and function descriptions, marking function bounds, and many other niceties. In this article I'll describe the process of reverse engineering the structure and contents of the PROM so that I could build the decompiler.

Background

The Silicon Graphics O2 is a Unix workstation with a MIPS CPU.

There are two families of CPUs available for the O2:

In the early 2000s, members of the Nekochan community replaced the 300 MHz RM5200 and 350 MHz RM7000A CPUs with a faster 600 MHz RM7000C model. The 600 MHz CPU, though in-order, is faster than the out-of-order 400 MHz R12000 CPU in most cases.

This modification is documented by SGI Depot in the article Upgrading an O2 to 600MHz (and beyond!). While replacing a BGA-mounted CPU takes significant tooling and expertise, the modification does not require any firmware or software changes.

The Problem

As the title ("Upgrading an O2 to 600MHz (and beyond!)") of the article might suggest, there were hopes of further upgrades. The article notes

Meanwhile, Joe unfortunately did not have any success with the PMC 866Mhz CPU - apparently it is not quite as compatible with R5200 as PMC thought. Meanwhile, any ideas about a 900 are somewhat hampered by the need to have a distinctly modified IP32 PROM image, which would need some assistance from SGI. Who knows if they would be willing to help; one can but ask!

Watch this space!!

The 900 MHz CPU referred to is the RM7900 from PMC-Sierra. The RM7900 uses a newer E9000 CPU core but in a 304-pin BGA package compatible with earlier RM7000 CPUs. It is not clear to me what the 866 MHz CPU is — I can find no evidence of an 866 MHz MIPS CPU, RM7000 or otherwise.

Presumably any attempts to use an RM7900 failed without support in the O2's PROM firmware.

At the time, Silicon Graphics still existed and there remained some faint hope for access to the source code of the PROM — the boot firmware — but today Silicon Graphics is long gone and with it the source code for the PROM. (as well as any concerns about legal issues from reverse engineering!)

The (partial) Solution

I reverse engineered the PROM firmware and wrote a program to decompile it into modifiable assembly (.S) files. The assembly files can be reassembled into a bit-identical PROM image, thus verifying that the decompilation was accurate.

With the PROM firmware now decompiled into modifiable assembly, the "distinctly modified IP32 PROM image" needed for RM7900 support is possible — no assistance from SGI required.

External Annotations

The assembly files are made more comprehensible with various annotations and other improvements to readability.

| Filename | Purpose |

|---|---|

| labels.json | Named addresses for branch targets and data |

| comments.json | Per-instruction documentation |

| functions.json | Function boundaries and descriptions |

| operands.json | Instruction operand replacements |

| relocations.json | Code that executes at different addresses than stored |

| bss.json | Named BSS (uninitialized data) symbols |

The resulting assembly:

| Without improvements | With improvements |

|---|---|

|

|

Reverse engineering the IP32 PROM

When I began this process, I knew only a tiny bit about firmware or the MIPS instruction set. I knew even less about the initialization process for MIPS CPUs.

First steps

A mailing list post in 2004 about the topic dissuaded others from reverse engineering the IP32 PROM due to the difficulty.

Modifying the binary is most assuredly way more difficult than gaining access to ip32PROM source and modifying it directly (and solving license issues). The level of change to the binary needed to make the ip32PROM detect a new CPU would require extremely detailed knowledge of the binary format the ip32PROM is in, SGI O2 systems, and how the PROM even functions. I'd wager a guess that a super-skilled SGI engineer might possibly pull this off, given enough caffeine.

I read this and wondered, how difficult could it actually be? It didn't seem like firmware from 1996 would be terribly complex.

I found a 512 KiB binary dump of the last version of the O2's PROM:

$ md5sum ip32prom.rev4.18.bin

c9725e036052cf1f3e6258eb9bc687fa ip32prom.rev4.18.binAnd disassembled it:

$ mips64-unknown-linux-gnu-objdump -D -b binary -m mips -EB ip32prom.rev4.18.bin | head

ip32prom.rev4.18.bin: file format binary

Disassembly of section .data:

00000000 <.data>:

0: 10000011 b 0x48

4: 00000000 nop

8: 53484452 beql k0,t0,0x11154The first two instructions looked legitimate, but the third looked unlikely to be a real instruction.

Further inspection of the disassembly indicated that there were real functions:

[...]

152c: 03e00008 jr ra

1530: 00000000 nop

1534: 90820000 lbu v0,0(a0)

1538: 00001825 move v1,zero

153c: 24840001 addiu a0,a0,1

1540: 10400006 beqz v0,0x155c

1544: 00000000 nop

1548: 90820000 lbu v0,0(a0)

154c: 24840001 addiu a0,a0,1

1550: 24630001 addiu v1,v1,1

1554: 5440fffd bnezl v0,0x154c

1558: 90820000 lbu v0,0(a0)

155c: 03e00008 jr ra

1560: 00601025 move v0,v1

[...]The jr and nop at 152c and 1530 end a function, and the lbu at 1534 starts a new function by loading from the a0 (argument 0) register. The jr and move at 155c and 1560 return from the function and copy a value into v0 which holds the return value. (This function is strlen).

strings showed meaningful data as well:

$ strings ip32prom.rev4.18.bin | head -n2

SHDR

sloaderI recognized that the first string ("SHDR") matched the odd looking instruction from the initial disassembly:

8: 53484452 beql k0,t0,0x111540x53484452 is "SHDR".

SHDR

Could this stand for section/segment header? What info was contained in the header?

0: 10000011 b 0x48

4: 00000000 nop

8: 53484452 # "SHDR"

c: 00004000 # unknown data

10: 07030100 # unknown data

14: 736c6f61 # unknown data

18: 64657200 # unknown data

1c: 00000000 # unknown data

20: 00000000 # unknown data

24: 00000000 # unknown data

28: 00000000 # unknown data

2c: 00000000 # unknown data

30: 00000000 # unknown data

34: 312e3000 # unknown data

38: 00000000 # unknown data

3c: 8cb4693c # unknown data

40: 00000000 # unknown data

44: 00000000 # unknown data

48: 100000d7 b 0x3a8

4c: 00000000 nop

[...]

3a8: 401a6000 mfc0 k0,$12

3ac: 001ad402 srl k0,k0,0x10

3b0: 335a0018 andi k0,k0,0x18

3b4: 235affe8 addi k0,k0,-24

[...]SHDR size

The header appeared to be bounded by a branch+delay slot in [0x00, 0x08) and [0x48, 0x50). These two chained branches lead to valid-looking code at 0x3a8.

That meant that the SHDR size was 72 bytes (including 8 bytes for the branch and delay slot before the "SHDR" magic number).

Strings

Interpreting the unknown data as ASCII found some additional strings:

736c6f61646572is"sloader". It's followed by 25 zero bytes (null terminator included), so this could be the name of the section in a 32-byte field.312e30is"1.0". It's followed by 5 zero bytes (null terminator included), so this could be the version of the section in an 8-byte field.

That left bytes [0x0c, 0x14), [0x3c, 0x48) unknown.

The four bytes in [0x0c, 0x10) looked like they might be a single element, but I didn't know what 0x00004000 (16384) was.

The four bytes in [0x10, 0x14) were 7310. The length of the string "sloader" is 7, and the length of the string "1.0" is 3. These were probably the string lengths of the name and version fields. I didn't know what the 1 or 0 bytes meant.

I had no idea what the data in [0x3c, 0x48) was.

I found that there were 5 instances of "SHDR" in the binary dump. The table contains the name and version in each header and their lengths (which matched the actual strings!).

| Offset | Name | Name Len | Version | Version Len |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0x00000000 |

sloader | 7 | 1.0 | 3 |

0x00004000 |

env | 3 | 1.0 | 3 |

0x00004400 |

post1 | 5 | 1.0 | 3 |

0x00009200 |

firmware | 8 | 4.18 | 4 |

0x00069200 |

version | 7 | 4.18 | 4 |

Section length

I recognized that the env section started at 0x00004000 — the same as the unknown [0x0c, 0x10) bytes in the sloader header. Was it the offset of the next SHDR? Or maybe the length of the current section?

Adding the unknown value to the offset of the current SHDR:

| Offset | Section | [0x0c, 0x10) | Offset + unknown |

|---|---|---|---|

0x00000000 |

sloader | 0x00004000 |

0x00004000 |

0x00004000 |

env | 0x00000400 |

0x00004400 |

0x00004400 |

post1 | 0x00004d44 |

0x00009144 |

0x00009200 |

firmware | 0x0005fffc |

0x000691fc |

0x00069200 |

version | 0x00000388 |

0x00069588 |

These unknown values looked to be the length of the current section, but maybe needed to be rounded up to the next 0x100?

Checksum

During this part of the investigation, I noticed that at the end of each section there was a bogus instruction, often preceded by a lot of zeros that looked to be padding.

[start of "sloader" section]

0: 10000011 b 0x48

4: 00000000 nop

8: 53484452 # "SHDR" for sloader

[...]

[a lot of zeros — padding]

3ffc: 15d0fa4f bne t6,s0,0x293c # Bogus instruction

[end of "sloader" section]

[start of "env" section]

4000: 00000000 nop

4004: 00000000 nop

4008: 53484452 # "SHDR" for env

[...]

43fc: eba16bb0 swc2 $1,27568(sp) # Bogus instruction

[end of "env" section]

[start of "post1" section]

4400: 10000011 b 0x4448

4404: 00000000 nop

4408: 53484452 # "SHDR" for post1

[...]

9140: 6c91c641 ldr s1,-14783(a0) # Bogus instruction

[end of "post1" section]

9144: 00000000 nop

[a lot of zeros — padding]

[start of "firmware" section]

9200: 10000011 b 0x9248

9204: 00000000 nop

9208: 53484452 # "SHDR" for firmware

[...]

691f8: d1c38847 lld v1,-30649(t6) # Bogus instruction

[end of "firmware" section]

691fc: 00000000 nop

[start of "version" section]

69200: 7f454c46 .word 0x7f454c46 # WTF?

69204: 01020100 .word 0x1020100 # WTF?

69208: 53484452 # "SHDR" for version

[...]

[a lot of zeros — padding]

69584: 108fedea beq a0,t7,0x64d30 # Bogus instruction

[end of "version" section]

69588: 00000000 nop

[a lot of zeros — padding]

69600:

[a lot of ones — padding]Those bogus instructions each end at the offset calculated by the SHDR start + the section length. They end the section. Could they be checksums for the section? If they're checksums, how are they calculated?

| Section | Checksum |

|---|---|

| sloader | 0x15d0fa4f |

| env | 0xeba16bb0 |

| post1 | 0x6c91c641 |

| firmware | 0xd1c38847 |

| version | 0x108fedea |

SHDR checksum

The SHDRs had some weird looking numbers towards the ends as well. Might they be checksums as well?

| Section | SHDR checksum |

|---|---|

| sloader | 0x8cb4693c |

| env | 0x131811ae |

| post1 | 0xc516c9e5 |

| firmware | 0x82b4a297 |

| version | 0x012d56b7 |

Section type

The remaining unknown bytes in the SHDRs were [0x12, 0x14), [0x40, 0x48). Their values for each SHDR are:

| Section | 0x12 | 0x13 | [0x40, 0x44) | [0x44, 0x48) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sloader | 1 | 0 | 0x00000000 |

0x00000000 |

| env | 0 | 0 | 0x4175746f |

0x4c6f6164 |

| post1 | 1 | 0 | 0x00000000 |

0x00000000 |

| firmware | 3 | 0 | 0x81000000 |

0x00048e70 |

| version | 0 | 8 | 0x00000000 |

0x00000000 |

From the names and small sizes of env and version I guessed that they did not contain code. sloader, post1, and firmware definitely did include code, and their SHDRs' initial instructions branched over their SHDRs to more code.

| Section | Entry instructions |

|---|---|

| sloader | branch over SHDR |

| env | nop |

| post1 | branch over SHDR |

| firmware | branch over SHDR |

| version | unknown1 |

strings confirmed that env and version were almost entirely ASCII data. In fact, 0x4175746f / 0x4c6f6164 are ASCII for Auto / Load.

I suspected that the value in byte 0x12 was the section type, with the lowest bit indicating whether the section was code (1) or data (0).

The sloader, post1, and firmware sections began with branch instructions that jump over the SHDR. The env section began with two nop instructions. The version section began with data that I only came to understand much later.

The byte at 0x13 is 0 in all SHDRs other than version. This is padding to a 4-byte boundary.

Trailing 8 bytes

I didn't figure out what the trailing 8 bytes were until much later in the process, but here's what I did know at this point.

envdidn't seem to have these bytes — as stated before the bytes immediately followingenv's SHDR are actual data that fit with the rest of the data in the section.versioncontained zeros for these bytes, but the next 12 bytes were as well so it wasn't certain whether they were metadata or actual data.sloaderandpost1contained zeros in these bytes, but their initial branch instructions jumped just past these fields. It seemed pretty clear that they were some metadata.firmwarewas the only one that seemed to clearly contain some meaningful metadata here (0x81000000/0x00048e70). Likesloaderandpost1, the initial branch instruction jumped just past these fields.

These findings seemed to correlate with the values in byte 0x12.

| Name | 0x12 | [0x40, 0x44) | [0x44, 0x48) |

|---|---|---|---|

| sloader | 1 | 0x00000000 |

0x00000000 |

| env | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| post1 | 1 | 0x00000000 |

0x00000000 |

| firmware | 3 | 0x81000000 |

0x00048e70 |

| version | 0 | N/A | N/A |

It seemed that if the lowest bit in byte 0x12 was set that the 8 bytes would be present, and the second bit indicated something about the metadata?

Summary

| Bytes | Field | sloader | env | post1 | firmware | version |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0x00-0x08) | Entry instructions | branch over SHDR | nop | branch over SHDR | branch over SHDR | unknown2 |

| [0x08-0x0c) | Magic number | "SHDR" | "SHDR" | "SHDR" | "SHDR" | "SHDR" |

| [0x0c-0x10) | Section Length | 16384 | 1024 | 19780 | 393212 | 904 |

| [0x10-0x11) | Name Length | 7 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 7 |

| [0x11-0x12) | Version Length | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| [0x12-0x13) | Section Type | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| [0x13-0x14) | Padding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 83 |

| [0x14-0x34) | Name String | "sloader" | "env" | "post1" | "firmware" | "version" |

| [0x34-0x3c) | Version String | "1.0" | "1.0" | "1.0" | "4.18" | "4.18" |

| [0x3c-0x40) | SHDR Checksum | 0x8cb4693c |

0x131811ae |

0xc516c9e5 |

0x82b4a297 |

0x012d56b7 |

| [0x40-0x44) | Metadata #1 | 0x00000000 |

N/A | 0x00000000 |

0x81000000 |

N/A |

| [0x44-0x48) | Metadata #2 | 0x00000000 |

N/A | 0x00000000 |

0x00048e70 |

N/A |

| [end] | Section Checksum | 0x15d0fa4f |

0xeba16bb0 |

0x6c91c641 |

0xd1c38847 |

0x108fedea |

Identifying Code

How

With the SHDRs mostly understood, I moved on to trying to understand the code.

It was evident that the code sections also included strings and other data. How could I programmatically identify what was code and what was data?

I turned to the Capstone disassembler — a small library with a simple interface capable of disassembling a large number of architectures' instruction sets, including MIPS.

In short, the decompiler part of the project began here with a program that essentially performed a breadth-first search of the code. It processed instructions, beginning with the first branch instruction in a code section, discovering more code in the process. If an address was reachable by a branch then it must be code and the program could search it for further branch targets.

The results were promising but unimpressive. Only around 10% of the binary was identified as code.

Relative jumps versus (nearly) absolute jumps

I discovered that there were a number of reasons for this, with the most salient being that I didn't understand jump instructions. While branch instructions are relative, jump instructions provide a (nearly) absolute jump target.

For example, the unconditional branch instruction (b) here jumps 0x48 / 72 bytes, regardless of its location in memory.

0: 10000011 b 0x48The jump-and-link (jal) instruction (used for function calls) provides the low 28-bits of the jump target (26-bits encoded, shifted left by 2) with the high 4-bits coming from its own address in memory.

6e0: 0ff0023c jal 0xfc008f0This meant that the 0xfc008f0 target was missing the high 4-bits, and without those I couldn't find the function it was calling.

I realized I didn't actually know where execution began.

I picked up a copy of See MIPS Run and found it to be an invaluable resource in this process. In it I found:

The CPU responds to reset by starting to fetch instructions from

0xBFC0.0000. This is physical address0x1FC0.0000in the uncached kseg1 region.

I'd answered an important question (and discovered that I didn't have any idea about MIPS' different memory regions — another thing I'd need to learn).

With this knowledge in hand, I disassembled the binary again but this time with the --adjust-vma=0xbfc00000 flag. The two instructions from earlier now disassembled as:

bfc00000: 10000011 b 0xbfc00048bfc006e0: 0ff0023c jal 0xbfc008f0A small change to the decompiler to tell Capstone the starting address resulted in it finding a lot more code.

Visualizing binary structure

Around this time, I recognized visualizing the binary structure could be useful.

I added support for emitting images in the simplest format I could find — XPM.

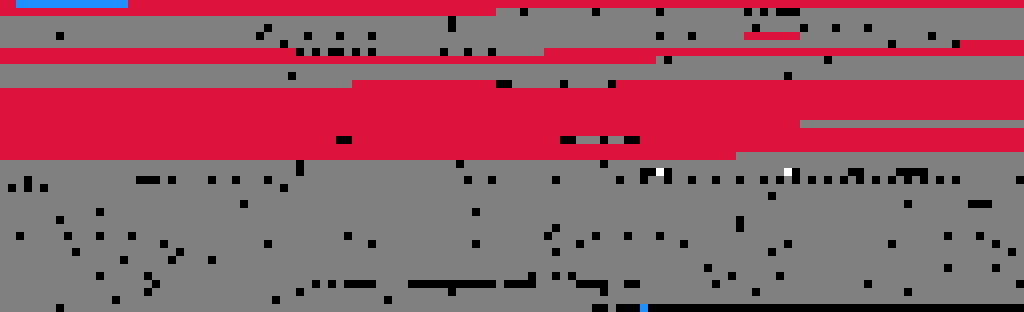

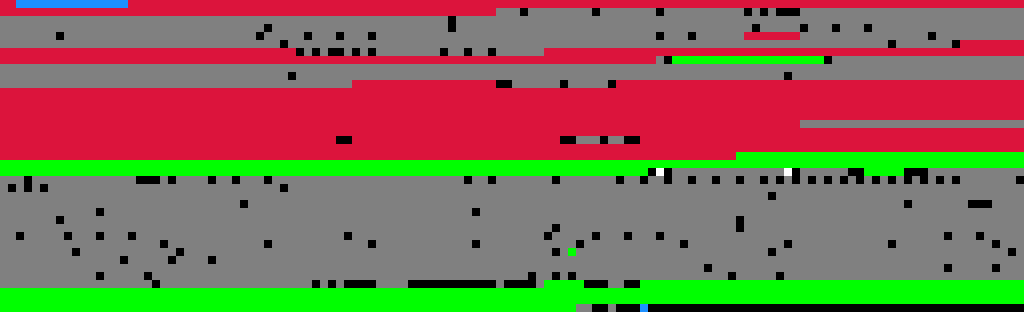

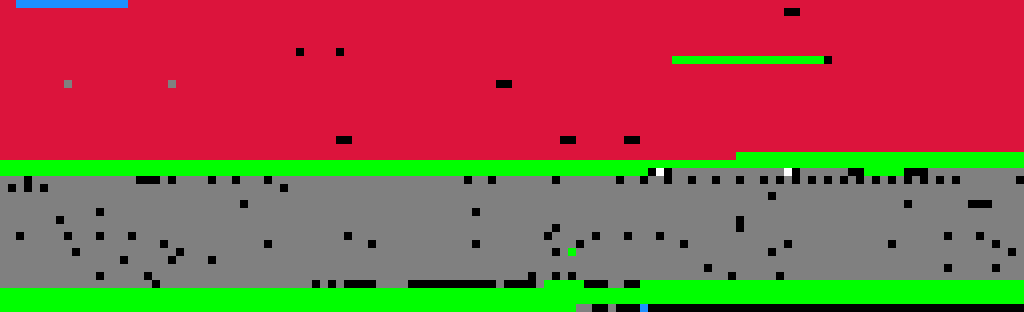

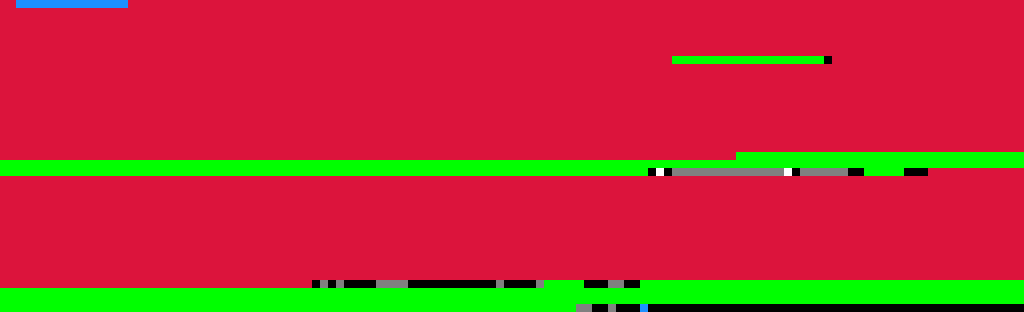

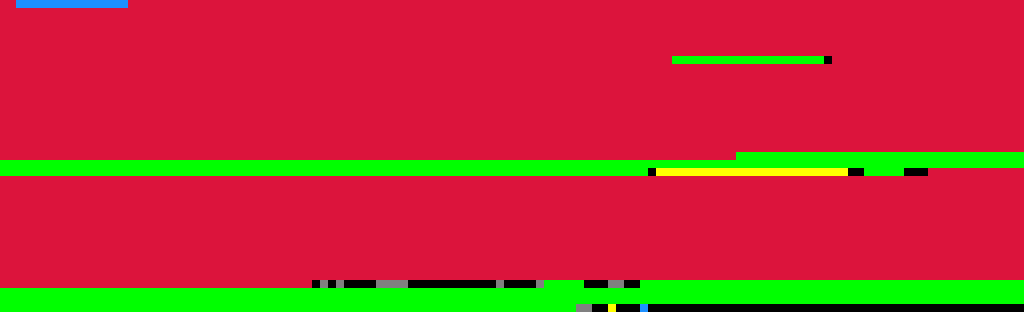

Here's what the post1 structure looked like:

Each row contained 128 pixels, with each representing a 4-byte chunk of the binary image. 4-byte chunks work well because MIPS instructions are 4 bytes and are always naturally aligned.

Red is code. Blue is header and checksum. Black is 0x00000000. White is 0xffffffff. Gray is unknown.

What was in the unknown areas?

Identifying Strings

strings indicated there was plenty of ASCII data in the binary, so I wrote some code to find it. It wasn't hard, but there were lots of corner cases to discover one by one.

The string data in sloader, post1, and firmware is always aligned to a 4-byte boundary. This was very convenient for finding the starting points and fit well with the existing visualization support.

Green is ASCII data.

Statically-unreachable functions

I could see valid instructions in the remaining unknown data. The functions hadn't been found for three reasons:

- called via a jump table

- called via a constructed address

- actually dead code

I added the annotation system for providing external information about the firmware and added the functions' addresses to functions.json. These labels would prepopulate the code discovery queue.

Virtual Subsection

The remaining large chunk of unknown data was code. But when I added annotations for the functions' addresses, code discovery failed because the functions contained jumps to addresses that were outside of the ROM. For example:

$ mips64-unknown-linux-gnu-objdump -b binary -m mips -EB --adjust-vma=0xbfc00000 -D -d ip32prom.rev4.18.bin \

| grep 'jal.*0xb000' \

| head

bfc072a0: 0c0010e1 jal 0xb0004384

bfc072c0: 0c0011f4 jal 0xb00047d0

bfc072d8: 0c001125 jal 0xb0004494

bfc072f0: 0c0011f4 jal 0xb00047d0

bfc07300: 0c001125 jal 0xb0004494

bfc0731c: 0c0011f4 jal 0xb00047d0

bfc07330: 0c0011f4 jal 0xb00047d0

bfc07554: 0c0011f4 jal 0xb00047d0

bfc075fc: 0c0011f4 jal 0xb00047d0

bfc0763c: 0c0011f4 jal 0xb00047d0It turns out (after a lot of assembly reading), the post1 section contains a blob of code that is copied to RAM and executed at a different address (0xa0004000). Adding support for dealing with this was a lot of work.

Unreachable Code

There were a few stray pixels in the middle of the code sections. The nop instruction on MIPS is 0x00000000, so I knew that the black pixels were nop instructions — typically padding between functions. The .int 0x00000000 in this snippet is an unreachable padding nop.

F_0xbfc05098: /* 0xbfc05098 */

cache (CACHE_TYPE_L1I|INDEX_WRITEBACK_INV), 0($a0)

nop

jr $ra

nop

.int 0x00000000But there were also bits of unknown data in the middle of code. Here's an example from post1.S:

beql $t6, $t8, L_0xbfc05824

addiu $v1, $s1, 2

b L_0xbfc05894

ori $v0, $v1, 0x100

.int 0x26230002

L_0xbfc05824: /* 0xbfc05824 */

lbu $t2, 2($s0)Whatever the instruction was, it was definitely unreachable since it occurred after an unconditional branch.

I added a pass that inspected unknown data in the middle of code sections and marked them as code with an unreachable comment.

beql $t6, $t8, L_0xbfc05824

addiu $v1, $s1, 2

b L_0xbfc05894

ori $v0, $v1, 0x100

addiu $v1, $s1, 2 # unreachable

L_0xbfc05824: /* 0xbfc05824 */

lbu $t2, 2($s0)It seems pretty clear that these unreachable instructions were the result of a compiler optimization that filled branch delay slots. The same addiu $v1, $s1, 2 instruction can be seen a few lines above in the delay slot of the beql instruction. Leaving these dead instructions behind looks like a (minor) compiler bug to me.

Accessed memory

I added a pass that marked memory addresses that were accessed by load and store instructions in yellow.

Remaining mysteries

firmware section

The firmware section accounts for 91% of the used portion of the PROM image (384 KiB of 422 KiB), and despite the success of decompiling the code in sloader and post1, the firmware section was still looking very sad. Here are the first 8 rows of the structure, with the rest not looking much different.

Looking at the small amount of successfully discovered code showed a jal instruction to an unknown address.

L_0xbfc092a4: /* 0xbfc092a4 */

move $a0, $s0

jal 0xb1000370

move $a1, $s1

b L_0xbfc092a4

nopAbsolute jumps like jal compose their target using the top four bits of their own address, which until now I'd assumed was 0xb (from 0xbfc00000). Clearly this must not be the case.

The firmware section is the only section with the 0x2 bit set in the section type field. I'd previously identified that this bit seemed related to the presence of meaningful-looking data in the 8 bytes immediately following the SHDR.

The first four bytes were 0x81000000. Maybe it was the address the code was expected to execute from?

This theory had merit for a few reasons:

- the low 28 bits of

jal's jump target were0x1000370, which would work when executing from0x81000000. - a virtual address of

0x81000000is within thekseg0virtual address space.kseg0is unmapped (virtual addresses are simply translated to physical addresses by dropping the high 3-bits), so it doesn't require initializing the TLB. It's also (configurably) cached, which is probably desirable for the core part of the firmware. - the physical memory location would therefore be

0x01000000, or 16 MiB — within the O2's minimum memory configuration of 32 MiB.

I tried disassembling the firmware section with --adjust-vma=0x81000000. The jal now looked like

810000a8: 0c4000dc jal 0x81000370and better yet, at 0x81000370 there appeared to be a function.

[...]

8100035c: 27bd0018 addiu sp,sp,24

81000360: 03e00008 jr ra

81000364: 00000000 nop

...

81000370: 27bdffd8 addiu sp,sp,-40

81000374: afb00018 sw s0,24(sp)

81000378: 00808025 move s0,a0

8100037c: afbf001c sw ra,28(sp)

81000380: afa5002c sw a1,44(sp)

81000384: 0c4013a6 jal 0x81004e98

[...]The second four-byte value was 0x00048e70 / 298608. I didn't recognize that this was the length until I happened to notice something odd:

[...]

81048e70: 81048e70 lb a0,-29072(t0)

81048e74: 0000b290 .word 0xb290

[...]The data at location 0x81048e70 was its own address?

Spidey senses tingling, I looked at what was at 0x81048e70 + 0xb290 + 8 (the size of this header) = 0x81054108.

81054108: 81054100 lb a1,16640(t0)

8105410c: 0000bee0 .word 0xbee0And again at 0x81054100 + 0xbee0 + 16 (the size of two headers) = 0x8105fff0.

8105fff0: 81000000 lb zero,0(t0)

8105fff4: 00000000 nopThis time, however, we were at the very end of the section. The remaining 8-bytes of the section were the checksum (0xd1c38847) and four bytes of zeros to pad to a 256-byte boundary.

8105fff8: d1c38847 lld v1,-30649(t6)

8105fffc: 00000000 nopSo these pairs appeared to be an address and length with the last pair as a sentinel value with a length of zero.

Inspecting the contents of each of these subsections showed clear differences. The first subsection was code. The second was primarily strings with what looked to be jump tables (sequences of pointers into the code's virtual memory area). The third was more difficult. It still had some strings. It still had some pointers to the code. But whereas all the memory accesses to the second subsection were loads, there were loads and stores to the third.

It became apparent that these were the .text, .rodata, and (read-write) .data sections.

| Subsection | Load Address | Length | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

.text |

0x81000000 |

0x00048e70 |

Executable code |

.rodata |

0x81048e70 |

0x0000b290 |

Read-only data (strings, tables) |

.data |

0x81054100 |

0x0000bee0 |

Read-write initialized data |

| sentinel | 0x81000000 |

0x00000000 |

Zero length terminates parsing |

Presumably the firmware section was written in C, compiled to a static ELF binary, and then had its sections extracted and repacked into a simple but custom format.

Checksum

If the ultimate goal of the project was to make modifying the PROM possible, I'd need to be able to recalculate the checksums.

Fortunately it wasn't too hard to find the function that verified the checksum in sloader.

is_section_checksum_valid: /* 0xbfc01874 */

lw $t6, SHDR_OFFSET_SECTION_LEN($a0) # $t6 = Load the length of the section

[...]

addiu $v1, $a0, SHDR_SIZE # $v1 = address of end of SHDR

addu $a1, $a0, $t6 # $a1 = address of end of section

[...]

move $v0, $v1 # $v0 = address of data to be checksummed

[...]

move $a2, $zero # $a2 = checksum

[...]

checksum_main_loop: /* 0xbfc018c4 */

lw $t9, 0($v0) # $t9 = word[0]

lw $t0, 4($v0) # $t0 = word[1]

lw $t1, 8($v0) # $t1 = word[2]

addu $a2, $a2, $t9 # checksum += word[0]

lw $t2, 0xc($v0) # $t2 = word[3]

addu $a2, $a2, $t0 # checksum += word[1]

addiu $v0, $v0, 0x10 # word += 16

addu $a2, $a2, $t1 # checksum += word[2]

bne $v0, $a1, checksum_main_loop # branch while not at end

addu $a2, $a2, $t2 # checksum += word[3]

checksum_done: /* 0xbfc018ec */

jr $ra

sltiu $v0, $a2, 1 # return checksum == 0A plain old two's complement checksum — add all the 32-bit words and negate, such that when the stored checksum is added the result is zero.

I verified that the SHDR checksum is calculated the same way. A funny implication is that the section checksum calculation doesn't need to consider the contents of the SHDR, because a valid checksum for the SHDR necessarily means that its contribution would be 0. We see this taken advantage of in is_section_checksum_valid by skipping the SHDR.

version SHDR

The version section's SHDR had three oddities compared with the others.

- the initial bytes looked like garbage

- the padding byte contained

8 - there was data after the

"version"string in the 32-byte name field

Initial bytes

The section didn't seem important for my purposes, so it wasn't until I was implementing support for recognizing addresses constructed by li + addiu/ori pairs that I discovered what the initial bytes were.

Some values constructed weren't addresses but other useful values:

133333000— a clock frequency31536000— the number of seconds in 365 days0x53484452— the "SHDR" magic value

This made me wonder if the initial bytes (0x7f454c46, 0x01020100) could be magic numbers.

A quick search revealed that 0x7f454c46 was the magic number for ELF binaries ("\x7fELF"). file on the extracted version section confirmed, and I felt a bit silly for not realizing this sooner.

$ file version.bin

version.bin: ELF 32-bit MSB MIPS, MIPS-II (SYSV)I looked up the structure of the ELF header, and found that the initial 16 bytes were the e_ident field.

#define EI_NIDENT (16)

typedef struct

{

unsigned char e_ident[EI_NIDENT]; /* Magic number and other info */

[...]

} Elf32_Ehdr;It contained the ELF magic number and the 0x01020100 value, which I decoded as:

Ehdr->e_ident[EI_CLASS] = ELFCLASS32;

Ehdr->e_ident[EI_DATA] = ELFDATA2MSB;

Ehdr->e_ident[EI_VERSION] = EV_CURRENT;

Ehdr->e_ident[EI_OSABI] = ELFOSABI_NONE;The remaining bytes in e_ident are ABI version (byte 8) and padding (9..15). These bytes contained the "SHDR" magic number and the section length.

Value in padding byte

With the recognition that the SHDR and ELF header were overlaid, I checked what was in the ELF header at this address.

| SHDR | ELF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bytes | Field | Interpretation | Field | Interpretation |

| 0x12 | Section Type | 0, SECTION_TYPE_DATA |

e_machine |

(0x08, EM_MIPS) |

| 0x13 | Padding | 8 |

||

A perfect fit.

Data after "version" name string

Decoding the stray data in the name string was trivial at this point.

Ehdr->e_phoff = 0x00000000;

Ehdr->e_shoff = 0x00000244;

Ehdr->e_flags = EF_MIPS_ARCH_2 | EF_MIPS_NOREORDER | EF_MIPS_PIC;

Ehdr->e_ehsize = 52;

Ehdr->e_phentsize = 0;

Ehdr->e_phnum = 0;

Ehdr->e_shentsize = 40;

Ehdr->e_shnum = 8;

Ehdr->e_shstrndx = 7;Conclusion

Reverse engineering the IP32 PROM turned out to be more tractable than the author of the mailing list post thought.

The firmware's structure — SHDRs, subsection headers, checksums — was relatively straightforward (in hindsight, at least), but it took small incremental steps over a long period of time to fully unmask.

Visualization was particularly helpful, not just for understanding but also providing motivation and a progress bar of sorts.

For a 512 KiB firmware image from 1996, the main challenge wasn't complexity but instead the sheer number of small details to get right.

Next steps

With the structure of the PROM fully understood, work turned to improving the decompiler's output.

The decompiler now produces assembly source files that reassemble into a bit-identical copy of the original ROM image — a strong confirmation that the PROM has been correctly understood. Today, with BSS variable names, function labels, and comments annotating the output, the firmware is sufficiently readable to understand its hardware initialization and boot process.

My hope is that this work is an important step towards a new CPU upgrade in the Silicon Graphics O2.

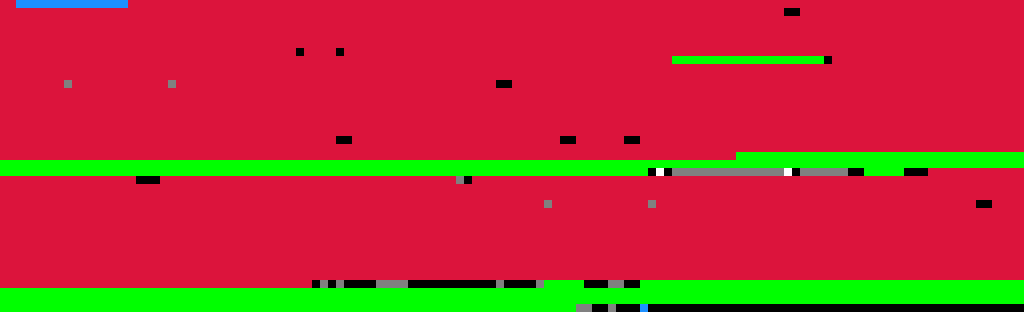

Current PROM structure

Here's the full structure of the PROM image, as generated by the decompiler at the time of this writing.

Red is code. Blue is header and checksum. Green is ASCII data. Yellow is accessed memory. Black is 0x00000000. White is 0xffffffff. Gray is unknown.

Footnotes

– Tags: mips reverse-engineering sgi